Scaling Options for EGA 320x200

The Problem

I spent some time today investigating the best way to draw an old EGA/VGA display

on a modern monitor, and also tried to identify the closest ScummVM settings to

any ideas I had. If you don’t care about all the analysis,

my personal conclusions are at the end of this post.

It’s harder than you might think to perfectly display an old DOS game on a modern computer. Old DOS games were typically displayed on a 4:3 monitor, in a 320x200 pixel grid of either 16 colors or 256 colors. Because there were so few pixels, and so few colors, often every pixel was drawn with a purpose. Coarse dithering is an instantly-recognizable aesthetic in old games, and I don’t want to lose that when playing them today.

However, resolutions today are much higher, so we need to scale the old game screens up to have a good experience. So, what’s the big deal? Just draw everything twice as large and call it a day, right?

Wrong. Modern pixels are square, and old DOS pixels were rectangles (taller than they were wide). That means, even displaying non-scaled 320x200 screens looks vertically squashed–everything is too short and fat.

So the question is: is there a way to scale up the game while simultaneously adjusting the

aspect ratio, without distorting the image? If so, what are the correct ScummVM settings

for that configuration?

DOS-era Pixel Shapes

Old CRT monitors had a 4:3 aspect-ratio, meaning that the screens were slightly wider than they were tall. So, at a resolution of 320x200 pixels filling that 4:3 space, we see that each pixel was:

- 4 units / 320 = 0.0125 units wide

- 3 units / 200 = 0.015 units tall

The ratio of width to height, then, is 125:150, or 5:6. The pixels are slightly taller than they are wide.

(note to self: in general you can take screen ratio/pixel ratio to get the overall

aspect ratio. So (4/3)/(320/200) = 800/960 = 5/6).

Correcting for Aspect Ratio

Modern pixels are square. My 16:9 1366x768 monitor’s aspect ratio is 0.9995, basically 1:1. So, if you take an old 320x200 image and just display it as-is, the output would have dimensions in a 4.8:3 ratio instead of 4:3 as it was originally seen. The picture will be vertically too small. So, what is the correct resolution?

Well, if we only care about the image having the right shape, then any multiple of 4:3 will do. So, examples would be:

| Scale Factor | Resolution |

|---|---|

| 4:3 * 80 | 320x240 |

| 4:3 * 100 | 400x300 |

| 4:3 * 120 | 480x360 |

| 4:3 * 160 | 640x480 |

| 4:3 * 200 | 800x600 |

| 4:3 * 400 | 1600x1200 |

Exact Integer-Multiple Scaling

Getting the right shape is the easy part. The hard part, is getting the right shape and not distorting the original pixels. As I mentioned in the intro, every pixel mattered in old games, so it would be a shame to distort them when stretching the image into the correct aspect ratio.

The best case scenario would be to scale up the image as an integer multiple in both directions. Then the image would have it’s original blocky look and keep the correct proportions. Unfortunately, since the 5 in 5:6 is a prime number, we can’t reduce the original aspect ratio any further, and the only pixel-perfect expansion of the original is: (320 * 5) x (200 * 6) = 1600x1200.

My laptop doesn’t come close to that, but there are some screens, such as some Microsoft Surface devices, with 1920x1280 that would be pretty much perfect for this. So, you heard it here first: Microsoft Surface 3 is the perfect DOS gaming machine!

Non-Exact Integer-Multiple Scaling

I’m clutching to integer-multiples of the original pixels because I don’t want to affect the crispness or “internal logic” of the artwork.

Let’s say we have a 4k display (3840x2160). Now the perfect 1600x1200 image of the last section is too small again, but we can’t simply double it. I think here, we just need to find a pair of integers that gets us close to the 5:6 ratio while still filling the screen.

The obvious choice here is, 8:10 (0.8), which is very close to 5:6 (0.83333), and would produce a scaled image of 2560x2000. The resulting image’s dimensions would have a ratio of 3.84:3 instead of the ideal 4:3. In other words: it would be slightly tall-and-thin, but still pretty close to the original.

Unfortunately, my laptop screen is 1366x768, so the options above do me no good. Further, the closest integer ratio I can get to 5:6 (0.833) that would fit my screen is 2:3 (0.667). That’s just as distorted as not stretching at all – 1:1 is short and fat while 2:3 is tall and skinny by about the same amount.

Stretching by Row-Doubling

So, for my current screen, the best option available has to be some kind of internal distortion of the image as it is scaled. The least-intrusive distortion I can think of is occasional row doubling–in other words, leaving the width alone and performing a nearest-neighbor interpolation on a stretched height.

Let’s take an example: If I scale up times 3 to 960x600, then after aspect ratio correction I still have 960 pixels across, but I need to fill 720 vertical pixels. That means, somehow I have to add 120 pixels to the height of the image. The easiest way I can think to do that is by doubling up 120 rows at even intervals throughout the scene.

The higher the resolution, the less noticeable the doubled lines are. To see why, first notice that–no matter what–you’ll be doubling every 5th row in the scaled-up image:

| Scale | Resolution | 4:3 Corrected | Doubled Lines |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1x | 320x200 | 320x240 | 40 (20%) |

| 2x | 640x400 | 640x480 | 80 (20%) |

| 3x | 960x600 | 960x720 | 120 (20%) |

| 4x | 1280x800 | 1280x960 | 160 (20%) |

You might initially think that doubling 20% of the lines would make the same amount of visual distortion in the outcome, but it’s not so. The difference is how irregular the doubling is in relation to the original pixels.

| Scale | Output Height Pattern | Normalized | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1x | [1 1 1 1 2] | [1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 2.0] | 0.40 |

| 2x | [2 2 3 2 3] | [1.0 1.0 1.5 1.0 1.5] | 0.24 |

| 3x | [3 4 3 4 4] | [1.0 1.3 1.0 1.3 1.3] | 0.16 |

| 4x | [4 5 5 5 5] | [1.0 1.2 1.2 1.2 1.2] | 0.10 |

The “height pattern” is the height of each pixel after scaling, which falls into a repeating pattern at every scale. You can see that, as the resolution increases, the pixel heights get more regular and vary by a smaller amounts.

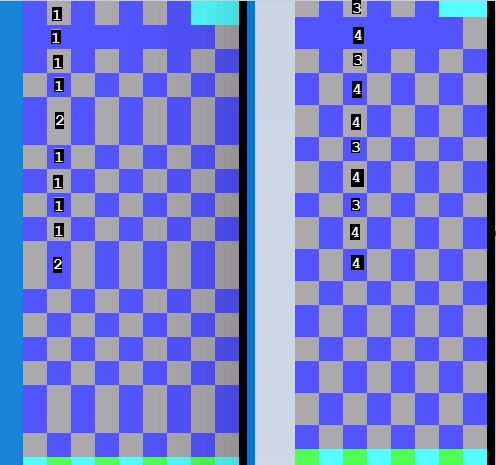

A picture might make the above explanation clearer. Fortunately, it looks like the

nearest-neighbor/doubling approach I’m describing is exactly what ScummVM does for

aspect ratio correction:

Above is a side-by-side comparison of a basic checkerboard dither for both 1x and 3x, as

rendered by ScummVM. I’ve labeled the height patterns so you can see they match the table. At 3x, the checkerboard is much more even overall; the distortions are spread out more evenly.

So, on my current 1366x768 screen, I can do 3x scaling, and the only time I really notice an issue is with multi-line text. Usually one line of text will look bolder than the rest because the horizontal lines in the letters are thicker than they were on the previous line. Again, it’s far less noticeable at 3x than it is at 2x or 1x.

Revisiting the 4k Monitor

Recall earlier I was thinking for a 4k monitor, a decent trade-off would be to slightly distort the overall aspect ratio, but keep a plain integer multiple of each source pixel. However, given how small the error looks when doubling every 5th line at high resolution, let’s revisit that.

A 4k monitor is 3840x2160. So, we can just barely fit a multiple of 9 on our original 320x200 image:

| Scale | Resolution | 4:3 Corrected | Doubled Lines |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9x | 2880x1800 | 2880x2160 | 360 (20%) |

| Scale | Output Height Pattern | Normalized | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9x | [10 11 11 11 11] | [1.0 1.1 1.1 1.1 1.1] | 0.04 |

To me, this makes line-doubling at the highest available resolution the best overall strategy.

What about Doubling in Both Directions?

If doubling in the vertical direction is so promising, why not double in the

horizontal direction as well? It looks like ScummVM has an option for that, as well,

which is a Stretch-Mode called “Fit to Window (4:3).” Note: when you use this, don’t

also use the “Aspect ratio correction.”

Frankly, for low resolutions, I think sticking to 2x or 3x is preferable, and keeping the error only in one direction. At higher resolutions, where the error introduced by doubling is so minor, I think turning this on and maximizing the window will give the best experience.

Conclusions

While I still have a lowly 1366x768 resolution, I believe these ScummVM settings are

ideal for a retro-EGA/VGA experience:

- Plain 3x scaling

- Render Mode: default (or select the one I want)

- Stretch-Mode: Pixel-Perfect Scaling

- Select the box for Aspect-Ratio Correction

With a significantly higher-resolution monitor, my ideal settings would be:

- Normal (no scaling)

- Render Mode: default (or select the one I want)

- Stretch-Mode: Fit to Window (4:3)

- Do not select the box for Aspect-Ratio Correction

Appendix: DOSBox

After reading this blog post on joshmccarty.com, I found the equivalent settings for DOSBox:

- surface: ddraw

- aspect: true

- scaler: normal3x

- fullresolution: 1366x768

… so that’s what I use there, now.